Comparing the floods of 2002 and 2013

Eleven years earlier, in August 2002, Dresden was one of the cities worst affected by the Elbe floods, and by the flash floods triggered by the River Weisseritz. The Elbe water level at the time reached 9.40 metres, and large parts of the city centre were flooded. Brown flood waters poured out of the train station, and even the Semperoper – the Dresden Opera House – was immersed in water. In 2013, the River Saale played a more significant role in the flooding, which moved the focal point of damage further west. Improved dyke protection on both the Elbe and the Weisseritz also had the effect of moving the flooding further downstream, so that Saxony-Anhalt and Lower Saxony became the areas worst affected.

In Regensburg too, improved mobile flood control paid dividends. Whereas in the last major flood in March 1988, the district of Stadtamhof had been completely awash, in 2013 it escaped with just small-scale flooding despite the higher water level. However, extensive dyke breaches further downstream along the Danube caused severe flooding in the area of Deggendorf.

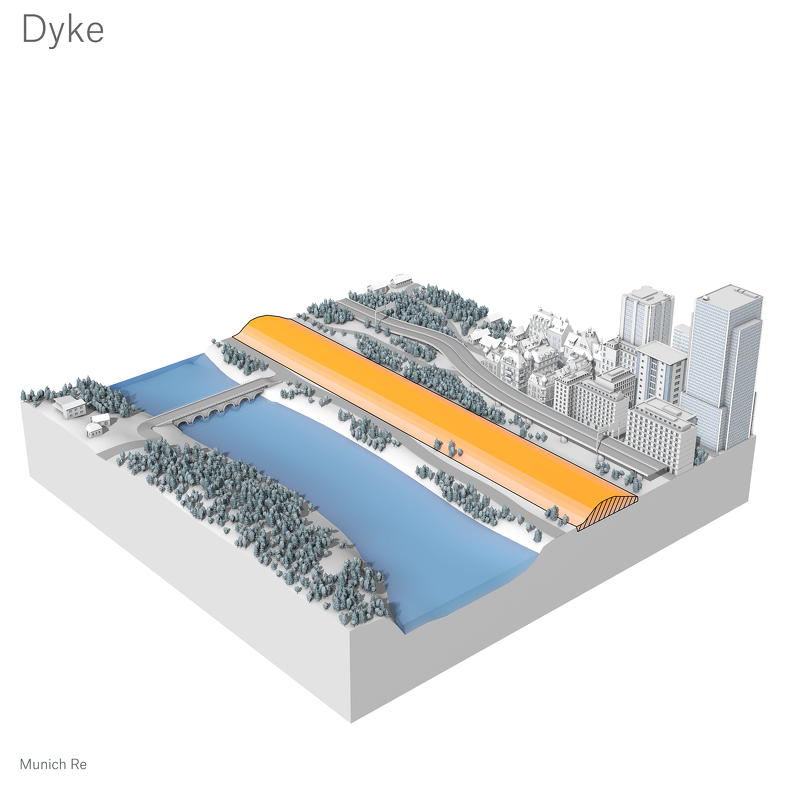

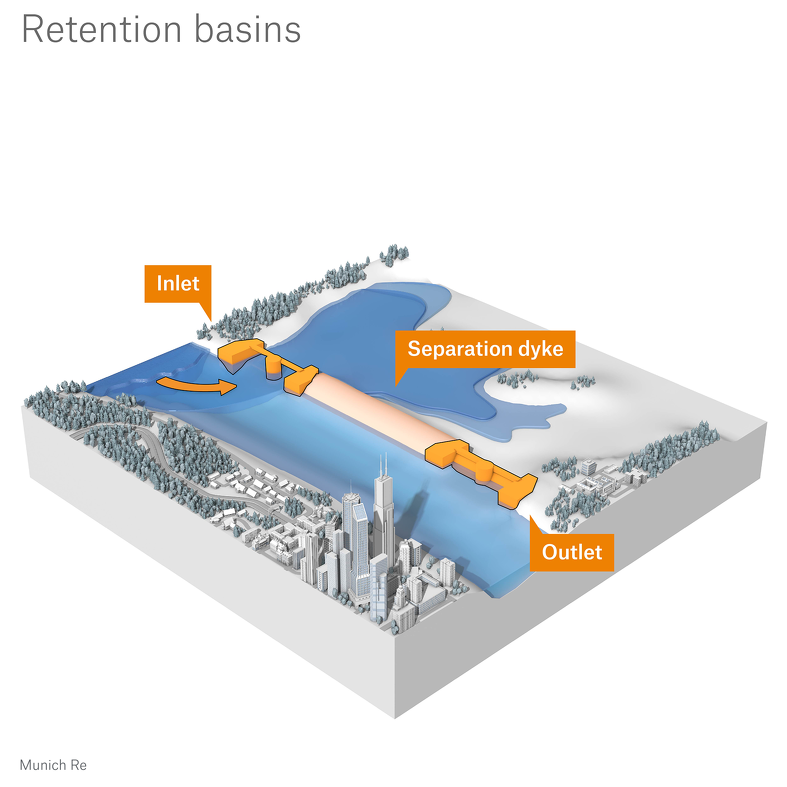

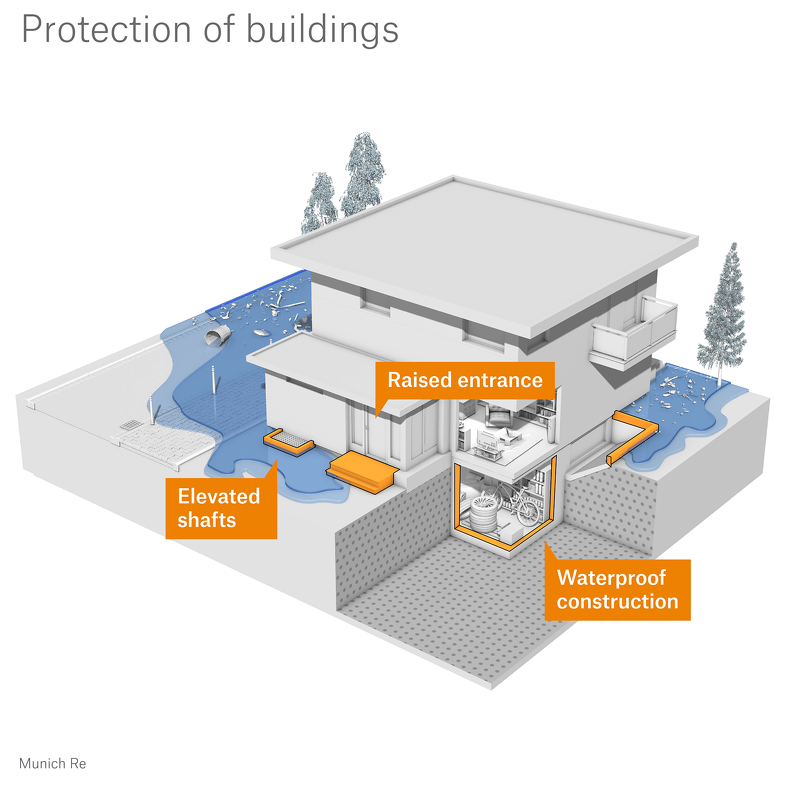

Two aspects are noteworthy from an insurance perspective. Technical protection against flooding has improved in many flood hazard zones. In the Elbe catchment area, dykes were rebuilt or reinforced, and mobile flood barriers held back the water masses in the Elbe, Danube and Vltava. In Dresden in particular, community preventive measures proved effective. For example, over the previous few years, the municipal water authority had made extensive structural, technical and organisational changes that allowed it to reduce the level of damage by 75% compared to 2002.

Protection against flood damage – What measures help?

Uninsured losses still high

At the same time, a major gap between economic and insured losses was again in evidence. In Germany, overall economic losses from the 2013 floods came to some €8bn, of which €1.7bn was insured. This insurance gap is largely attributable to the fact that most homeowners had no natural hazard insurance. On a national average, just 33% of property owners had this type of insurance in 2013. While this was more than in 2002 (18%), there were still major regional variations: about 40% of homeowners in Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia were insured against flood risks, but the rate in Bavaria was just 21% and as low as 13% in Lower Saxony.

There are various reasons for the prevailing underinsurance. In the past, there was a lack of adequate insurance cover, especially in highly exposed regions. In less exposed areas there was a lower level of risk awareness, and accordingly less demand for insurance solutions, not least because the government used to assume the bulk of losses suffered by private individuals and businesses.

Joining forces for greater risk awareness

Since 2013, federal states, insurance associations and the insurance industry have adopted numerous measures to increase risk awareness among homeowners and businesses.

- The governments in virtually every federal state have launched extensive information campaigns. In addition, the State of Bavaria has announced that, from 1 July 2019, it will no longer provide emergency financial aid following natural disasters to victims who could have purchased insurance.

- The insurance industry has expanded its portfolio, and now offers individual insurance solutions for the “Zürs 4” flood zone, as does ERGO, Munich Re's primary insurance arm.

- The German Insurance Association (GDV) regularly updates and improves its flood zones. It is currently developing a hazard zone for flash floods.

Climate change: More torrential rainfall not necessarily driving losses

The consensus among scientists is that climate change is influencing rainfall patterns in Europe. Observations over the last few decades and model projections for the future show a declining trend for summer precipitation in central Europe away from the coasts, whereas winter rainfall is tending to increase. Intense precipitation causing rivers to burst their banks is expected to occur more frequently in the winter half-year as climate change progresses. But in summer too, an intense precipitation event (such as that produced by a weather pattern with an extensive low-pressure system over central Europe) is certainly capable of triggering floods and high losses, as it did in 2002 and 2013. In addition, these events fall into a special category of persistent weather patterns, which have been increasing in frequency for some decades in the northern hemisphere summer half-year. There are strong indications that climate change is partly to blame for the increase in such weather patterns.

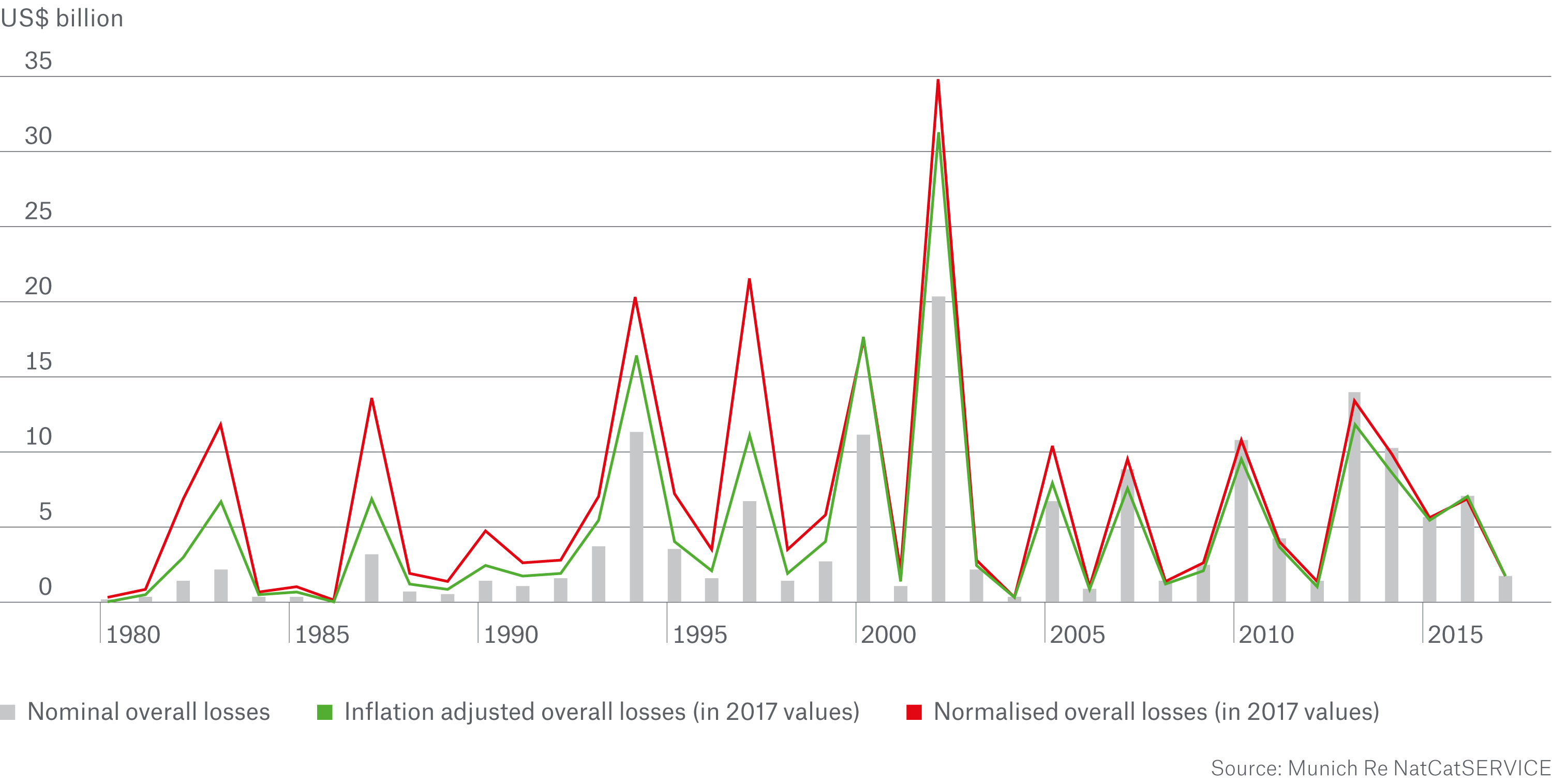

In general, more recent research expects that, as climate change continues, the number of weather events capable of producing river flooding and damage will increase in large parts of central Europe. Does this mean that flood losses will also increase sharply in the future? Not necessarily. Protective mechanisms such as dykes and early-warning systems are now extremely sophisticated and can be developed even further. Since 1980, flood losses in Europe (after adjustment for increases in value) have actually fallen.

Summary: Natural hazard insurance should be standard throughout Germany

Munich Re Experts

Related Topics

properties.trackTitle

properties.trackSubtitle