By mid-February, almost 10 million square kilometres of bush and forest in Queensland, New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory, Victoria, and South Australia had been razed, with some 3,000 homes and a large number of outbuildings devoured by the flames. The number of homes destroyed was even higher than in the Ash Wednesday Fires in 1983 or the Black Saturday Fires of 2009.

The fire season also produced record loss amounts: overall losses came to around US$ 2bn, of which around US$ 1.5bn was insured due to the high proportion of fire insurance cover for buildings. Overall losses were almost 50% higher than in 2008/09, the previously most destructive summer on record (US$ 1.4bn after adjustment for inflation). Even allowing for an adjustment of the 2008/2009 losses according to the change in destructible wealth since then, losses in the latest fire season were higher.

Climate change is fuelling wildfires in Australia over the long term

Conditions that favour wildfires have been on the rise for decades in southeastern Australia. Increases in maximum temperature are a key driver. In combination with slightly lower rainfall, this results in soil and vegetation drying out faster. In turn, this means there is a greater amount of combustible vegetation and more favourable weather conditions for bushfires to ignite and spread. As an example from Victoria, the level of the McArthur Forest Fire Danger Index (FFDI) in spring, which also includes factors such as wind speed, when averaged over the last 20 years, was well above the long-term average since 1950, as were the maximum recorded temperatures.

2019 saw the warmest December since measurements began. The average maximum temperature across the continent exceeded 40 degrees on 11 days during the month. Prior to December 2019, there had been only another 11 such days on record in Australia since 1910. A new scientific analysis using climate models concluded that the fire exposure in southeastern Australia has increased by at least 30% since 1900 as a result of climate change. Since the authors presented this as the lower limit, the true increase could be much higher. There are more studies which demonstrate that climate change is likely to have had a significant influence.

Natural climate variations act like a switch

The general long-term trend towards higher fire exposure due to climate change is heavily compounded in Australia by the effects of short-term natural climate variations. Both the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) and the Southern Annular Mode (SAM) influence rainfall, temperature, and wind over the continent. In the 2019 cool season, a strongly positive IOD phase led to a drought in southeastern Australia. On top of this, a largely negative SAM phase between September and December produced extremely hot and dry winds gusting from over the desert. As a yardstick for the fire risk, the FFDI was sometimes twice the long-term average or more in southeastern regions worst affected by the fires. For Australia as a whole, the value measured in the spring was higher than ever before.

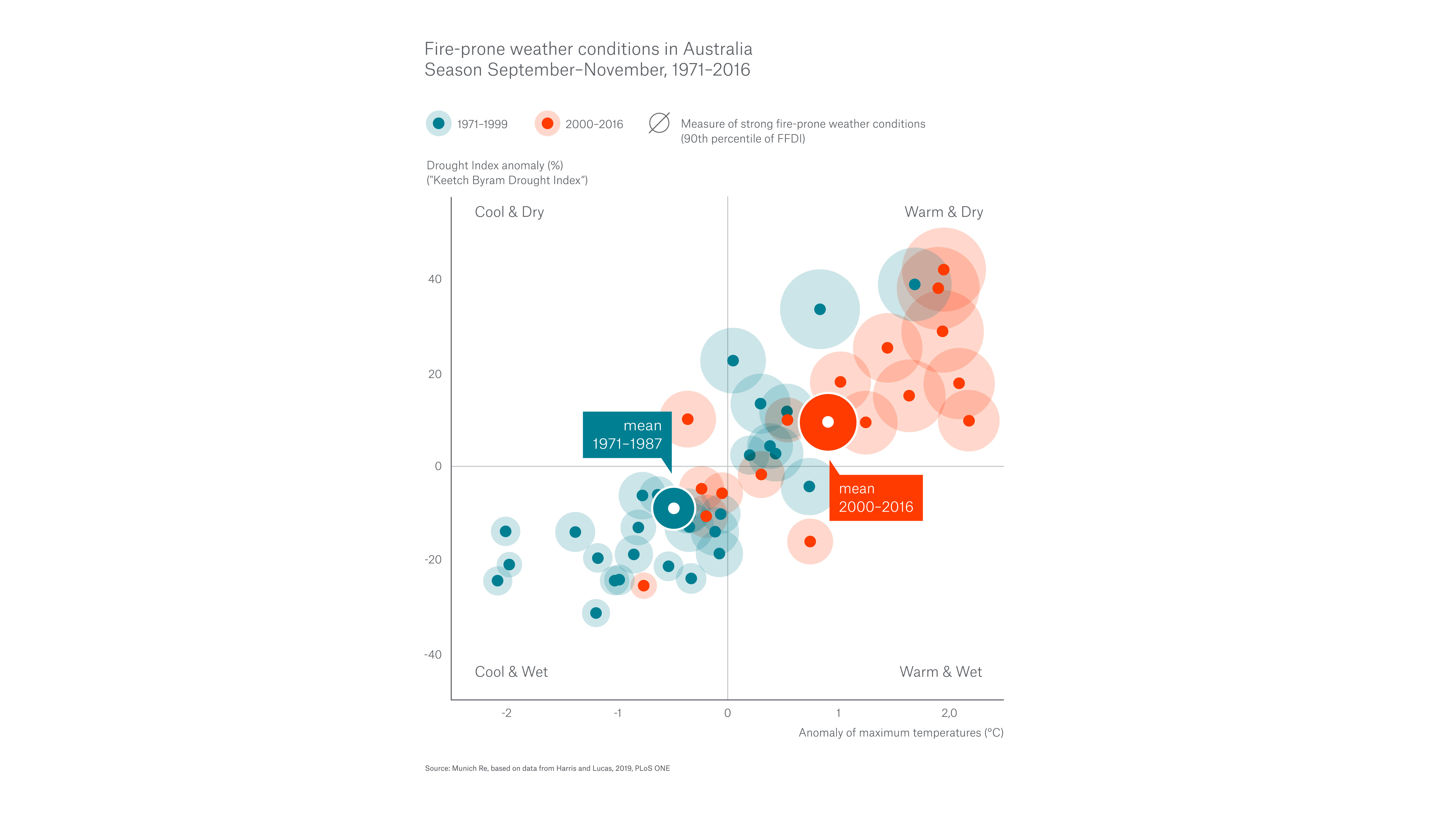

The following picture emerges if we link all the relevant weather factors for severe fire hazard in southeastern Australia up to 2016: seven of the ten years with the greatest spring fire-weather index (FFDI) were between 2000 and 2016. These years tended to be hot and dry, whereas earlier (after 1971) there was a higher proportion of cooler, wetter years with a lower level of bushfire hazard.

Climate change should be included in risk management

The analysis of the latest fires and the background conditions clearly shows that climate change needs to be included in the assessment of bushfire risks in Australia. Historical data can no longer form the sole basis for the assessment. Instead, an analysis of the recent period and future projections is critical. For assessments from one season to the next, knowledge of the natural climate cycles is also important, which will help for the forecast of seasonal fire weather conditions.

Given the devastation involved, loss prevention has become extremely important. At the interface between bush and settlements, it is crucial to maintain an adequate buffer zone between combustible vegetation and buildings and other structures of value through land-use planning measures, and to apply fire-resistant construction methods. These prevention measures decrease the likelihood of bushfire-related total losses.

Preventing fires in the first place is a further essential factor in averting losses. Unlike other natural disasters, bushfires are often started by people. The quantity of combustible dead and living vegetation that could fuel fires in the bush should also be reduced in risk areas. Given the fact that climate change is likely to increase the wildfire risk in Australia, these prevention measures will become more important than ever in future.

Downloads

Munich Re Experts

/Joanna-Aldridge-1456x1456.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/crop-1x1-400.jpg./crop-1x1-400.jpg)

Related Topics

properties.trackTitle

properties.trackSubtitle