Author: Mark Bove, Meteorologist & Natural Catastrophe Solutions Manager

Twenty years have passed since Hurricane Katrina became the most destructive hurricane in US history, producing an inflation-adjusted US$ 205 billion in overall losses, of which roughly half was insured.

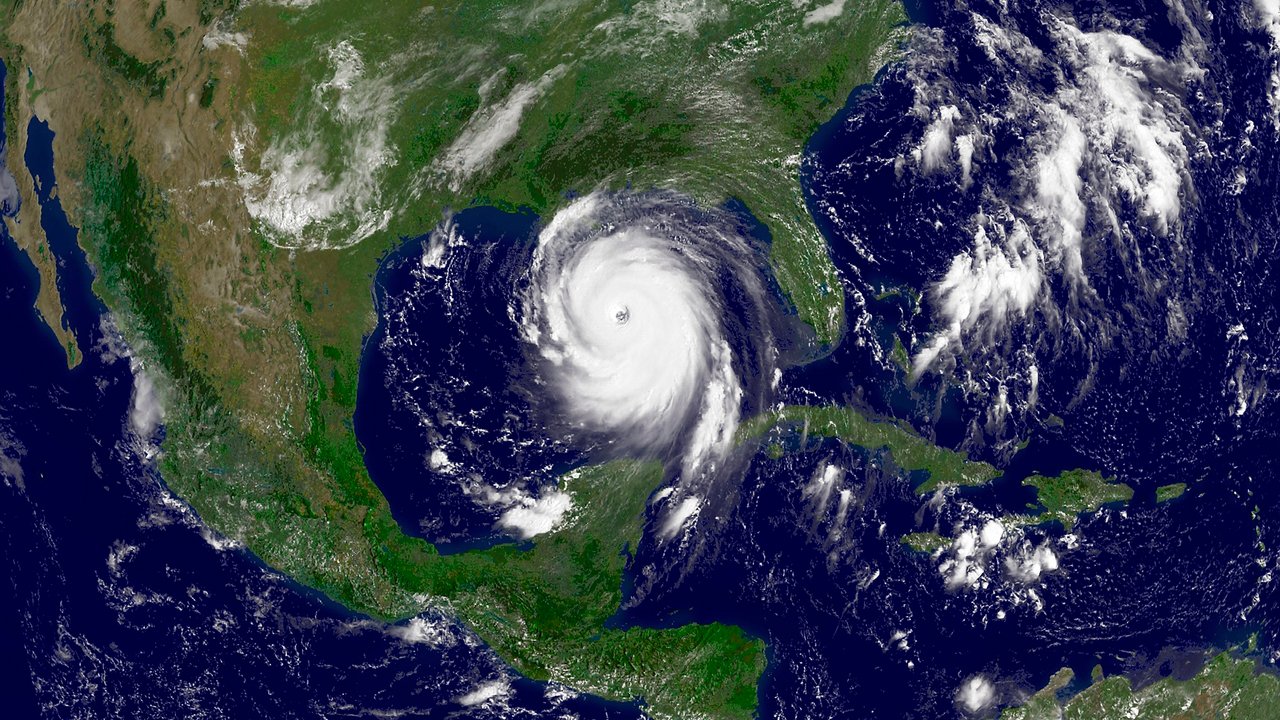

After an initial landfall in South Florida on August 26, 2005, Katrina intensified rapidly over the warm waters of the central Gulf of Mexico, reaching Category 5 on the 1-5 Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. Although the storm weakened before landfall in Louisiana on August 29, Katrina was still powerful enough to cause widespread wind damage in New Orleans and across the Mississippi Gulf Coast.1

Even more devastating was Katrina’s storm surge, a massive wall of water that inundated over 200 miles (320 km) of coastline stretching from Louisiana to the Florida panhandle, with maximum flood heights of 30 feet (10 meters) along the Mississippi coast. In (mostly below sea level) New Orleans, the storm surge overtopped and breached the city’s levee system. With no electricity to power the city’s pumping stations, the city flooded – and remained flooded – for weeks afterward.1 More than 1,800 people perished as a consequence of the storm – making Katrina one of the deadliest U.S. hurricanes on record as well.2

How has hurricane risk along the northern Gulf Coast changed since Katrina? By framing the question around the three components of risk: hazard, exposure, and vulnerability, we find that the risk is increasing:

- Hazard: Risk of major hurricane landfall for the northern Gulf Coast is increasing with time, including greater storm surge impacts due to sea level rise and land subsidence.

- Exposure: Like most coastal communities, values at risk in coastal Mississippi and the New Orleans metropolitan area continue to rise due to both socioeconomic trends and inflationary factors.

- Vulnerability: Adoption of statewide building codes in Louisiana has improved the wind resiliency of newer residential structures, but Mississippi’s patchwork approach to codes has led to only modest improvements. Post-Katrina upgrades have made New Orleans’ flood defense systems more resilient, but its effectiveness will erode over time due to subsidence and sea level rise.

Let’s look at each of these three components in more detail.

Hazard

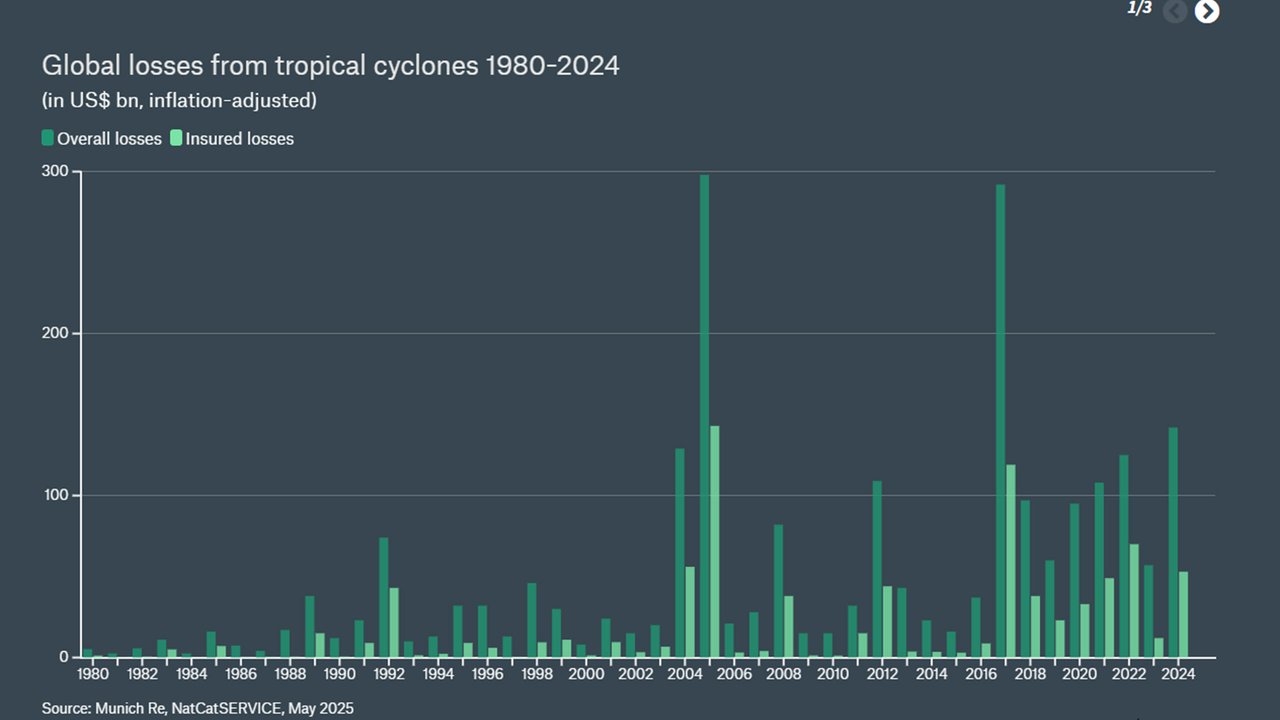

The exceedingly active 2004 and 2005 Atlantic hurricane seasons saw seven major hurricanes (Category 3 or higher) hit the U.S. over the span of 15 months.3 This flurry remains unprecedented in the U.S. historical record since 1900. There had been only seven major hurricane landfalls in the U.S. in the two decades prior to 2004. After collectively causing nearly half a trillion dollars of inflation-adjusted overall damage, the question was whether these years were an anomaly or harbinger of future trends. Twenty years later, it is safe to say that the 2004 and 2005 seasons remain outliers, as the long-term average of major U.S. landfalls post-2005 is just below the long-term average of 0.53/year.

While it’s impossible to predict hurricane tracks and possible landfalls far in advance, the key factors that drive tropical cyclone frequency are well understood. Warm ocean water is hurricane fuel, and this fuel intensifies as ocean temperatures rise. A tropical wave or storm that passes over an area of very warm ocean has a greater chance of storm formation or rapid intensification. Another key factor is wind shear, the change in wind speed or direction with height in the atmosphere. If upper-level winds blow in the opposite direction of a hurricane’s motion, shear can prevent development or intensification. Conversely, low shear environments can facilitate storm development and intensification.4

Overall tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic Basin, including the proportion that reach major hurricane status, has increased since 1995. But why? One hypothesis identifies naturally occurring cyclic changes in Atlantic sea surface temperatures as a possible mechanism, responsible for the increase in tropical cyclones seen since 1995 and the rather inactive period between 1970 and 1994. A second hypothesis proposes that increases in oceanic heat content – driven by climate change and a reduction in upper tropospheric pollution – is the cause. These hypotheses are not mutually exclusive, and the current scientific consensus is that both likely play a role in increased Atlantic tropical cyclone frequency since 1995.5

Few locations on Earth have warmer ocean temperatures than the Gulf of Mexico during peak hurricane season, and the unique geography of the basin means that any storm that develops or moves into the Gulf is almost assured a landfall. And as the Gulf continues to warm, the potential for major hurricanes making landfall along the Gulf Coast will increase as well.

Exposure

The population of the New Orleans metropolitan area remains about 13% (roughly 150,000 residents) below the city’s pre-Katrina levels, with the greatest drops in population in the heavily flooded parishes of Orleans (particularly the economically disadvantaged Lower Ninth Ward), Plaquemines, and St. Bernards.6a-6c However, New Orleans’ continued vital economic role as a port and tourist mecca drove an influx of investment, resulting in almost no drop in home values in the city post-storm. Twenty years later, home values in Orleans Parish are 75% greater today than in 2005.7

In coastal Mississippi, population and exposure growth in beachfront locales like Harrison, Hancock, and Jackson counties are growing faster than the rest of the state. Even though many beachfront-adjacent homes and businesses in Mississippi were never rebuilt after Katrina, the buildup of new property exposure outside of surge zones over the past 20 years has increased the state’s wind risk.8

Vulnerability

Assessments of wind damage after the seven major hurricanes in 2004 and 2005 indicated that new construction in Florida – built to the newly implemented 2002 Florida Building Code – outperformed similar construction in Mississippi and Louisiana, which did not have statewide wind codes.9 Later Florida hurricanes, like Irma (2017) and Ian (2022), would further confirm the effectiveness of Florida’s wind codes in reducing structural damage to homes and businesses.10

After Katrina and then Rita (which followed less than a month after) devastated Louisiana, the state legislature adopted the 2006 International Residential Code (IRC) for one- and two-unit dwellings in the state, including stricter wind load requirements near the coast.11 Since then, the state has continued to strengthen its wind code and code enforcement and is now among the top five U.S. hurricane states for resilient construction, per the 2024 Institute for Business and Home Safety (IBHS) “Rating the States”12 assessment. This means that the newest homes built in Louisiana are significantly more resilient to wind impacts, thereby reducing damage and increasing life safety in areas where storm surge is not a major threat.

Immediately after Katrina, Mississippi also considered but did not adopt statewide wind codes. It did, however, strengthen building codes for five coastal counties.13 The state finally passed a statewide wind code in 2014, but it allows counties and communities to opt out. That option creates disparate wind codes across the state, limiting the law’s overall effectiveness. More recent legislation in Mississippi requires licensing of building contractors. While this will help improve the resiliency of new construction, the state remains one of the most vulnerable to tropical cyclone wind impacts.12

Newer construction built to Louisiana’s new code fared well during several additional hurricane landfalls since Katrina and Rita, including three major hurricanes over the past 6 years. However, asphalt shingle roofs over 10 years in age have tended not to perform well and continue to be a significant loss driver from intense windstorms.14

Surge vulnerability

Wind damage can be successfully mitigated through proper building codes and code enforcement. Storm surge, on the other hand, can only be mitigated via elevating properties or building a flood barrier. While the latter is useful for protecting entire communities or large industrial facilities, flood barriers are typically unfeasible for individual residential properties, especially in areas where storm surges can exceed 30 feet (10 meters) in height.

Along the Mississippi beachfront, the challenges of rebuilding within a storm surge zone are made apparent by the hundreds of empty lots where homes once stood. Of the homes that were rebuilt, many were repaired at the same elevation, as the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) does not require elevating a home with less than 50% damage. But for homes damaged beyond that point, elevating the replacement becomes mandatory, an additional cost that many residents likely couldn’t afford.15

The levees and flood barriers that comprise the Great New Orleans Hurricane & Storm Damage Risk Reduction System (HSDRRS) underwent significant repairs and upgrades after Katrina – a US$ 15 billion investment in the region’s flood defense infrastructure, completed in 2018.16 Combined with repairs and upgrades to local groundwater pumping stations, the system is designed to mitigate flooding within the city for flood events with an 1% annual probability of occurrence (a so-called “100-year” flood). Although the New Orleans metro area has not experienced a significant surge event since Katrina, the system has been able to help mitigate rainfall-driven flash flooding from recent tropical cyclones.

It is expected, however, that the effectiveness of the HSDRRS will decrease with time. The system was designed to protect against a “100-year” flood in the year 2011. But since then, local relative sea level has risen by 2.5 – 3.5 inches (6 - 9 cm).17 This means that the system is less effective against a “100-year” flood in 2025. And as time goes on, changes in sea level and land subsidence will further undermine the effectiveness of the system by reducing their effective height. Furthermore, uneven rates of land subsidence along some levees are likely putting additional physical strain upon the system, potentially threatening structural integrity over time and increasing the risk of failure if no repairs are made.18

Related Topics

Contact our experts

Newsletter

properties.trackTitle

properties.trackSubtitle