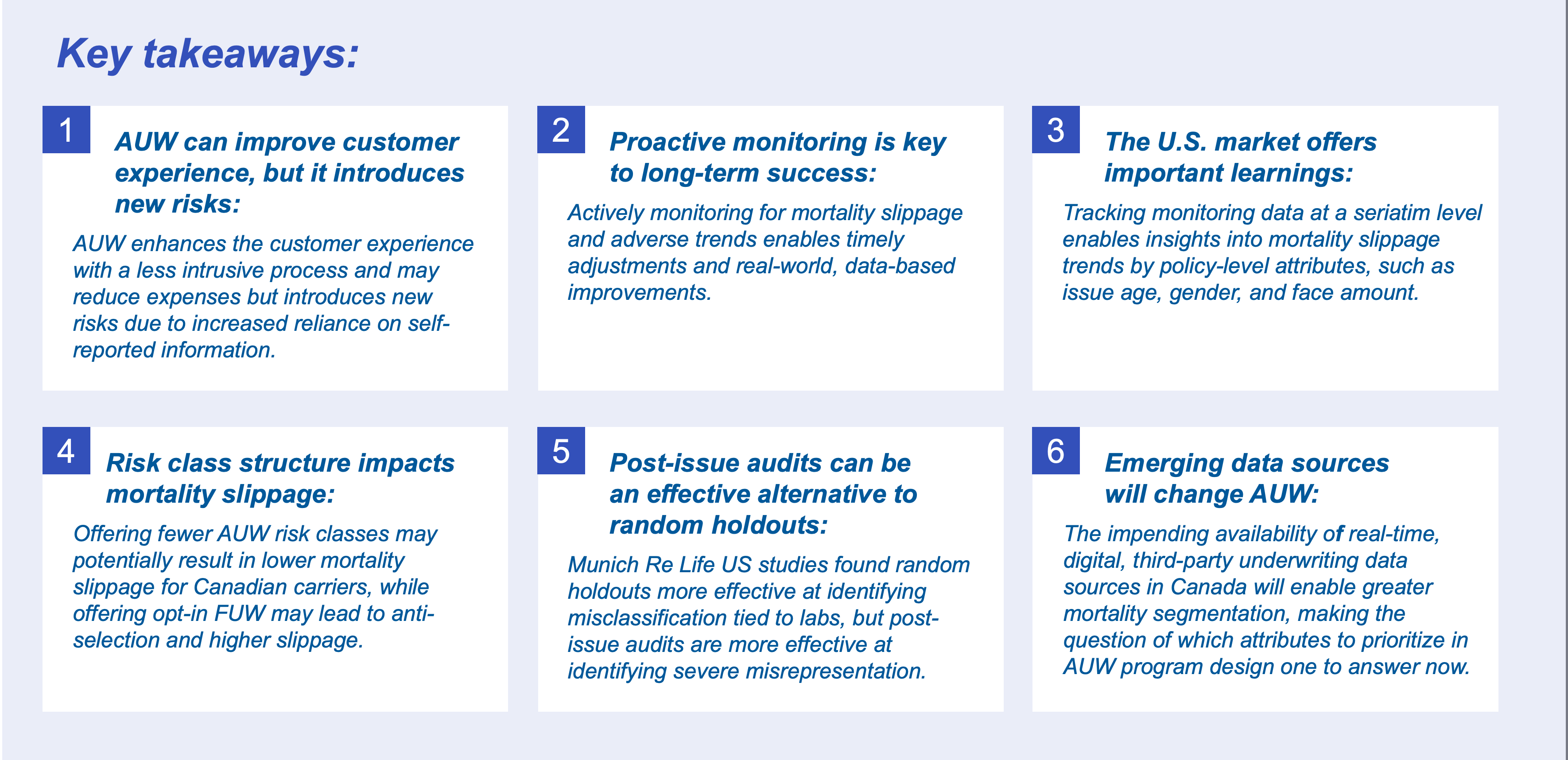

AUW continues to evolve and become more established in life insurance underwriting. While AUW improves customer experience over FUW, the reliance on self-reported information on BMI, tobacco use, medical history, and other health details introduces challenges for insurers. Removing traditional underwriting requirements could lead to:

Deteriorated mortality from attracting applicants who might not have applied or who would have been declined under traditional underwriting

Lost premiums due to assigning more favourable risk classifications than traditional underwriting

Both effects can be estimated by calculating mortality slippage, which is the difference between the mortality implied by the accelerated risk class and the mortality implied by the risk class they would have been issued under full underwriting.

Background on U.S. monitoring practices

Although Canadian AUW programs were established as early as 2015, it will still take time for enough credible claims experience to emerge so that we can see the true impact of AUW on mortality. In the meantime, it is crucial that insurers proactively monitor their AUW programs now to obtain early indicators of future mortality experience, so that they can react quickly to monitoring findings to improve programs and close potential loopholes. We can look to the U.S. for guidance, where AUW started earlier and is more widespread. In the U.S., two types of monitoring practices are commonly used:

Random holdout (RHO): Applicants that normally would have been underwritten with minimal evidence beyond the application and/or tele-interview are randomly selected to undergo additional underwriting requirements, such as fluids and vitals.

Post-issue audit (PIA): Known as post-issue underwriting in Canada, PIA typically involves reviewing an attending physician statement (APS) or electronic health record (EHR) after an AUW policy is issued. In the case of material misrepresentation, a PIA could result in policy rescission. The risk class decision made through PIA is considered a proxy for FUW.

Both monitoring practices enable insurers to compare risk class decisions through the AUW workflow to decisions through the FUW process (or a proxy, in the case of PIA). Insurers can quantify mortality slippage based on the risk class decision differences observed through a random sample of either monitoring practice.

This Munich Re Life US article about its 2023 mortality slippage study provides further details about U.S. monitoring practices.

Mortality slippage calculation

The relative mortality (RM) assumed in the slippage calculation directly impacts the results. In particular, declines have the highest misclassification severity and often drive the level of mortality slippage in practice, so results are highly sensitive to the RM assumed. 500% was chosen for ease of illustration in the example, but carriers can assume appropriate RMs for their own business.

In the simplified example above, all policies were assigned an equal weight as the calculation was done on a count basis. In practice, insurers can refine their slippage calculations to further distinguish RM based on policy-level characteristics such as age, sex, face amount, and product, and vary the weight of each record by the present value of expected claims.

Trends observed in a U.S. mortality slippage study

In the U.S., monitoring data is often tracked at a seriatim level, which allows for additional analysis of slippage by policy-level characteristics. A recent mortality slippage study published by Munich Re Life US showed the following trends by sex, issue age, and face amount.

Sex: Males generally have higher levels of misclassification than females in AUW programs. The average mortality slippage observed in males is more than 25% higher than that of females.

Issue age: Older issue ages are associated with higher mortality slippage (shown in Figure 1), as they typically have more impairments and, thus, more opportunities for misrepresentation. The protective value an insurer foregoes by waiving fluid testing and exams has a higher impact for older issue ages.

Face amount: Mortality slippage generally decreases as face amount increases (shown in Figure 1). This is likely driven by more stringent accelerated underwriting requirements and human underwriter review at higher face amounts. It could also result from differences in target market and/or demographics across the face bands.

Canadian considerations

Differences in AUW risk class structure could lead to lower mortality slippage for Canadian insurers

One factor impacting mortality slippage is the difference between the U.S. and Canadian AUW risk class structure. Life insurance carriers in Canada typically offer only two AUW risk classes (Non-Smoker and Smoker) whereas U.S. carriers usually replicate the full range of Preferred risk classes (typically four Non-Smoker and two Smoker classes) in their AUW programs.

This leads to a simpler AUW slippage calculation for Canadian clients due to the absence of AUW-Preferred class misclassifications. Interestingly, it may lead to lower mortality slippage numbers as the absence of AUW-Preferred risk classes in the Canadian market results in the absence of adverse Preferred misclassifications. Adverse Preferred misclassifications are cases where a policy receives a Preferred risk class under AUW but would have been issued Standard (or a lesser Preferred class) under FUW. Since these cases do not exist in the Canadian market due to the absence of multiple preferred risk classes, we expect lower mortality slippage numbers relative to the U.S., all else being equal.

In fact, a recent Munich Re Life US study found that about 70% of adverse RHO findings consist of Standard risks under FUW incorrectly receiving Preferred or Super Preferred rates under AUW. While these Preferred misclassifications have lower mortality impact than other forms of AUW misclassification, we expect that the absence of the most common misclassification source may decrease the mortality slippage estimated based on RHOs within the Canadian market relative to U.S. companies.

Canadian carriers exploring adding AUW-Preferred offerings should keep in mind that this may result in a higher prevalence of misclassification, leading to higher mortality slippage within their AUW programs unless protective measures are implemented. These could include predictive models for risk triage or the addition of new health data sources such as clinical labs or prescription drug data, both of which are well used in the U.S.

The above assumes the U.S. and Canadian markets see equal rates of misrepresentation and non-disclosure. It also ignores the role of Preferred opt-in programs, which are not widely available in the U.S., where policyholders can elect to go through FUW if they believe it would result in a better underwriting outcome. This could result in anti-selection and an unhealthier AUW applicant pool in Canada. The adverse impact that Preferred opt-in programs can have on mortality slippage should be considered in AUW program design.

Post-issue audits may be a valuable approach for monitoring Canadian mortality slippage

As mentioned in the earlier section on U.S. practices, RHO and PIA are the two main approaches to monitoring mortality slippage. The U.S. market places a far greater emphasis on PIA, while in Canada the vast majority of mortality slippage monitoring is conducted through RHO.

Sixty-three percent of U.S. carriers conduct PIAs using APS and/or EHRs, compared with only 19% of Canadian companies responding that they have or are currently exploring adding PIAs to their underwriting process.1

But does this market difference align with the strength of each of these monitoring techniques?

Recent studies by Munich Re in the U.S. found that RHOs are more effective at identifying adverse Preferred misclassification and misclassification directly tied to insurance labs, e.g., smoker non-disclosure, whereas PIAs are most effective at identifying the most severe forms of misrepresentation such as missed declined and rated cases, based on medical histories found in an APS or EHR. PIAs also offer better overall customer experience and potentially higher straight-through processing (STP) rates. Figure 2 shows the misclassification severity breakdown by monitoring method in the U.S. study.

Given the absence of Preferred AUW classes and, hence, the absence of adverse Preferred AUW misclassification in the Canadian market, one would expect PIAs to be relatively more effective in the Canadian context, given the benefits of using them to identify the forms of misclassification, such as missed declined policies.

Additionally, PIAs are seen in the U.S. as offering a better customer experience than RHOs, since they allow for more instant decisions given that additional evidence is collected for fewer applicants at the time of underwriting. Using PIAs in place of RHOs can also potentially decrease wastage.

Further to this point, above-average wastage on holdouts could be an indicator that a company’s AUW program is disproportionately attracting adverse risks and that the subsequent wastage is selective. In this case, RHO results are no longer truly random, as they represent a skewed proportion of applicants who were willing to provide evidence. PIAs avoid the potential for this anti-selection as direct action by insurance applicants is not required.

PIAs can also be a helpful tool for monitoring agent misrepresentation, although care should be taken in interpreting results, as they have been found to bring about more conservative risk class assignments than the traditional FUW process.

It is also worth noting that PIAs are often used on a more targeted basis in high-risk cases since this can provide more protective value if carriers are willing to rescind cases showing material misrepresentation. Findings from targeted audits are not suitable for monitoring mortality slippage as the targeted sample will not be representative of the overall business mix within an insurance channel.

Since RHOs and PIAs can have various implications with respect to advisor experience, required consents, and overall customer experience, there are many trade-offs to consider when selecting the right approach to mortality slippage. But early AUW monitoring results from the U.S. indicate that PIAs may add value in monitoring mortality slippage within the Canadian market.

Differences in underwriting data availability may change everything

Future considerations for shaping AUW program design

What data should be collected and why?

Lack of digitization and real-time access to underwriting data can be barriers for some Canadian carriers in segmenting AUW program risk, both in offering instant decisions on policies and monitoring mortality slippage. Given that data collection itself can pose a challenge in AUW, it raises the question of what data attributes should be prioritized when designing AUW programs.

From the mortality slippage perspective, the two most important data attributes to collect are the AUW and FUW risk classification on every case flagged for RHO. Having both allows for the calculation of the misclassification matrix shown above. FUW risk class is easy to identify as it is simply the final underwriting decision on an application where fluids have been collected through the RHO process. Some carriers are unable to capture AUW risk class for RHO cases due to a process flow that does not assign it for some of the policies routed for FUW via RHO. Below are some solutions for these cases.

One way to streamline the collection of AUW risk class is to exclude all AUW ineligible cases from the RHO sample. To add more context, one reason for not assigning AUW risk class for FUW-routed RHOs is that UW disclosures may automatically trigger the ordering of labs for some cases (e.g., disclosed diabetes). It can be difficult to attribute the risk class to the AUW process disclosures because the underwriting evaluation is based on both the disclosures and the insurance labs in tandem. Since cases with disclosures that automatically trigger labs are routed for FUW, they should not be considered AUW eligible, so we recommend carriers exclude these applications from their mortality slippage calculation.

Another solution is using a different approach for mortality slippage tracking, such as comparing smoker disclosure and decline rates between the AUW block as a whole versus all RHOs. This gives valuable block-level insights, but ensuring an apples-to-apples comparison requires care since RHO policies tend to be taken disproportionately from older ages and higher face amounts. This approach is a good first step if AUW risk class is not available, but it still has limitations in that it does not allow for policy-level mortality slippage analysis.

Another question to consider is where it makes the most sense to apply RHOs in the AUW process. Should they be assigned before or after applying rules engine and models to the population?

Assigning RHO at the beginning allows insurers to assess the efficacy of their underwriting triage models and evaluate the overall applicant pool risk. Conversely, assigning RHO after applying models, rules engines, and other risk assessment tools gives the best residual mortality slippage estimate since the cases that have already gone through the full risk assessment process are the ones that would have been issued at their assigned AUW risk class.

With this in mind, we believe it makes the most sense to do both! RHO assignment should be done at the beginning of the underwriting process, but other models and rules should be applied to all cases irrespective of whether they are flagged as RHOs. This allows insurers to assess individual tool effectiveness within their AUW program as well as the residual mortality slippage. However, we understand there are technical limitations that can sometimes impede tracking RHO assignment throughout the underwriting process. In this situation, we recommend applying RHOs as the last step in the process to give the best visibility into the residual mortality slippage.

In short, assessing individual AUW tool efficacy as well as overall program mortality slippage is important, but understanding overall program slippage should take priority if that presents technical challenges.

How policyholder-level data can shape program design

Typically, AUW programs in Canada deploy both targeted and random holdout programs where testing levels for both vary by age and amount, with more testing at older ages and higher face amounts.

Targeted holdouts (THO): A targeted holdout is a case in the No Fluid underwriting workflow that is selected for additional requirements (e.g., fluids, vitals, and/or non-routine APS) using underwriting analytics.

Absent direct data on mortality slippage, it is reasonable to expect that mortality risk would be greatest for these higher ages and amounts, but directly collecting policy-level assessments on mortality slippage allows for holdout levels to reflect the observed mortality slippage risk. For example, we saw above how U.S. studies show that mortality slippage increases with age but decreases by face amount.

This highlights how having custom holdout levels by underwriting data attributes, such as disclosed BMI, other underwriting disclosures, or distribution channel, may lead to holdout programs that better balance mortality slippage with customer experience. Tying mortality slippage directly to underwriting disclosures also allows for the possibility of expanding instant decisions to low-risk impairments. This application of slippage studies is still emerging but remains an exciting area to investigate.

Of course, AUW programs should still find a balance between customer and advisor experience and mortality slippage risk, but varying holdout levels by attributes other than age and amount can achieve a more ideal balance between risk and customer experience.

A proactive approach is key

References

Contact

This may interest you

properties.trackTitle

properties.trackSubtitle