Drug Abuse Mortality in the Insured Population

properties.trackTitle

properties.trackSubtitle

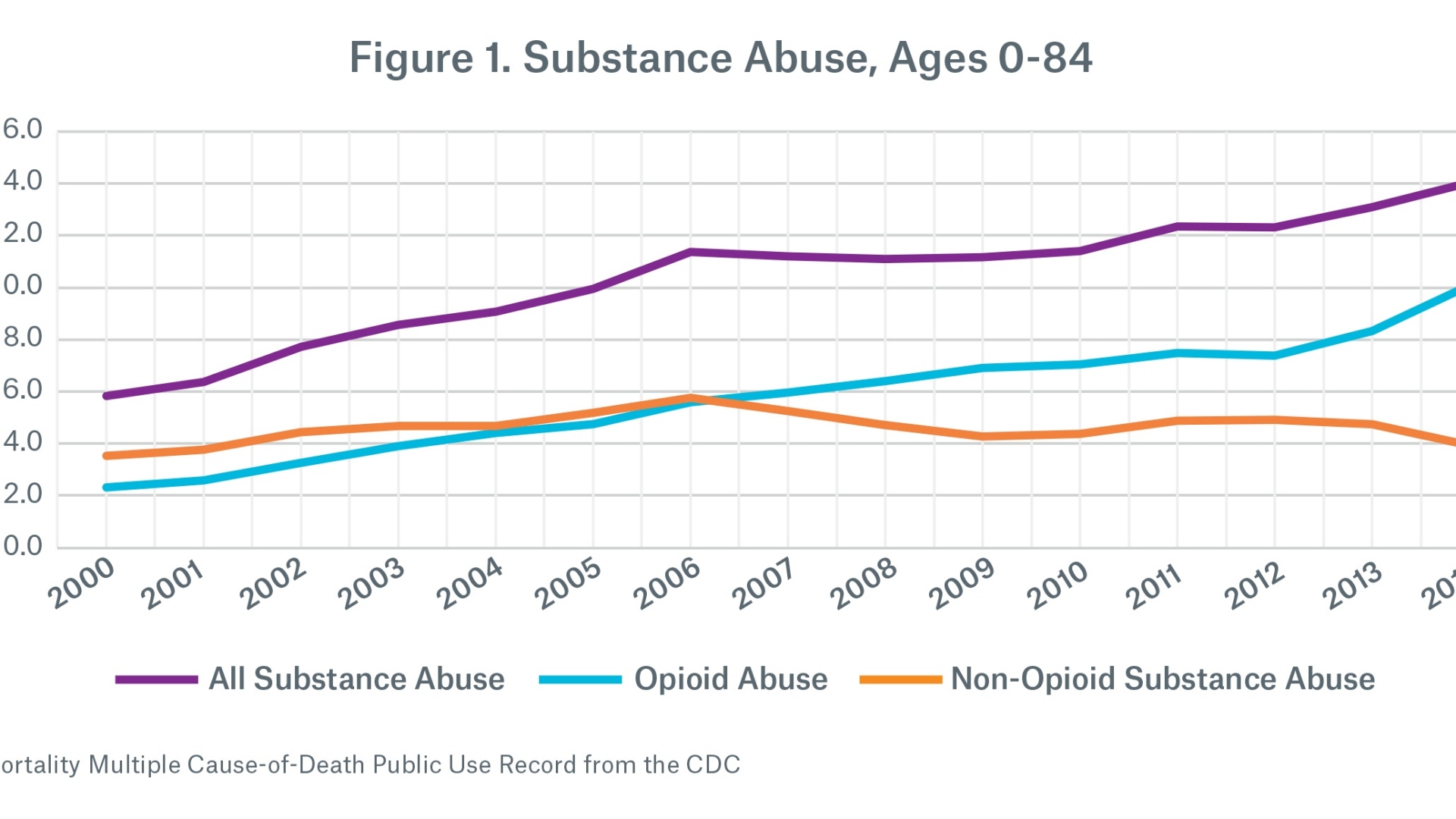

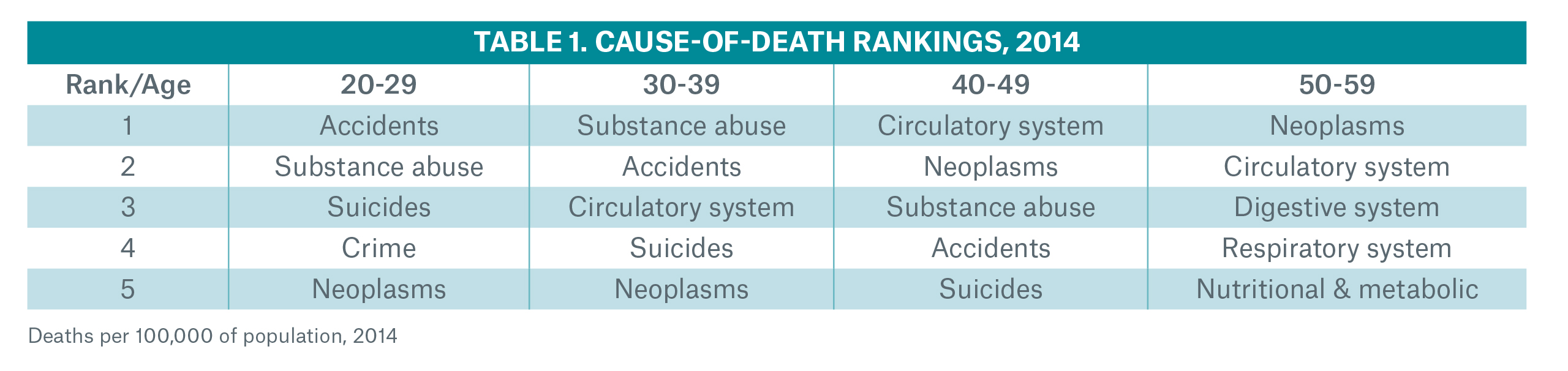

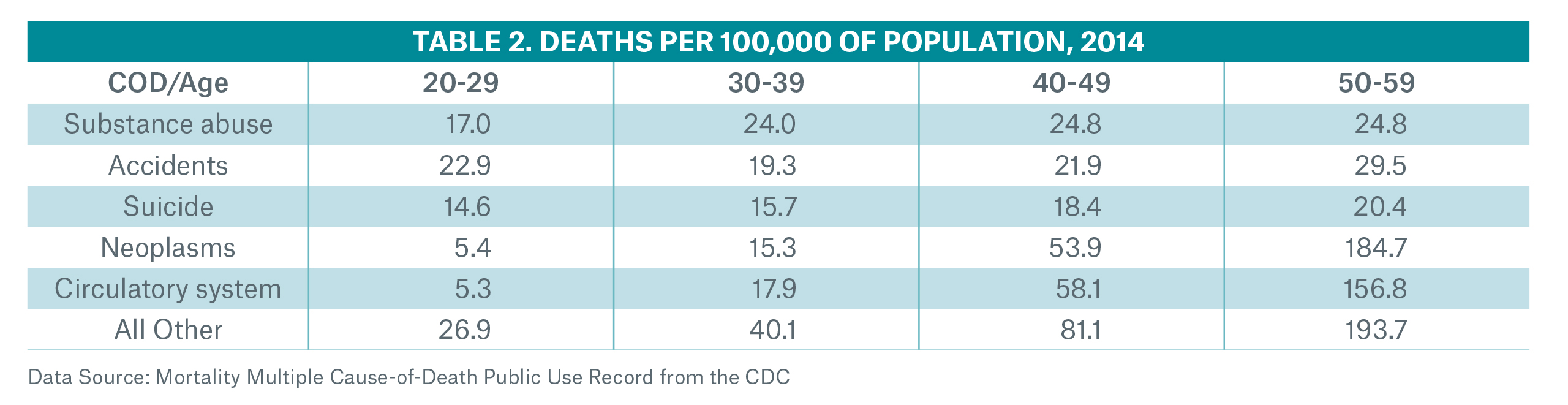

The substance abuse epidemic, especially from prescription and non-prescription opioids, is well publicized.1 Population data show that drug-related mortality rates have more than doubled since the beginning of the century. This statistic is troubling enough as it is, but it hides the fact that almost all the increase is due to opioids, which account for just over half of the deaths. Shockingly, mortality rates related to prescription and non-prescription opioids have quadrupled over the same period (Figure 1). In fact, substance abuse was the number one cause of death for those in their 30s in 2014 (see Tables 1 and 2, next page). As a consequence of these trends, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has published new guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain2 and the President has signed an executive order creating a federal commission to investigate and combat this crisis3.

Such a public health crisis certainly deserves this level of national attention. However, this paper seeks to look at the crisis through the lens of a life insurance company. Increasingly, underwriting departments are under pressure to decide whether or not to add opioid marker screening to blood profile exams; however, they may not have enough claims data to make this assessment, especially regarding a single cause of death. They need to be able to answer questions such as: Will this epidemic materially increase claim costs? Is the trend in the general population mortality indicative of what we expect to see in the insured population? Is there protective value under the current underwriting requirements or do underwriters need to take additional measures in order to guard against adverse-selection risks? We will explore these questions and propose a means to analyze them using readily available data.

We will focus our analysis at the substance abuse level, not specifically drilling down to opioids. Due to the way the cause of death is recorded in the databases, drilling down any further could lead to a higher level of misclassification risk. However, Figure 1 shows that almost all of the increase in drug-related mortality over the period being considered comes from opioids, so conclusions drawn at this level should reasonably translate to the subset of opioid abuse.

We used two main data sources in this analysis: first, the Mortality Multiple Cause-of-Death Public Use Records from the CDC, and second, Munich Re’s proprietary cause of death experience study. The CDC data were based on the general U.S. population and included more than 460,000 deaths from substance abuse between 2000 and 2014. Munich Re’s study was based on life insurance claims data and comprised more than 1,400 deaths from 2006 to 2015.

A socio-economic view of the crisis

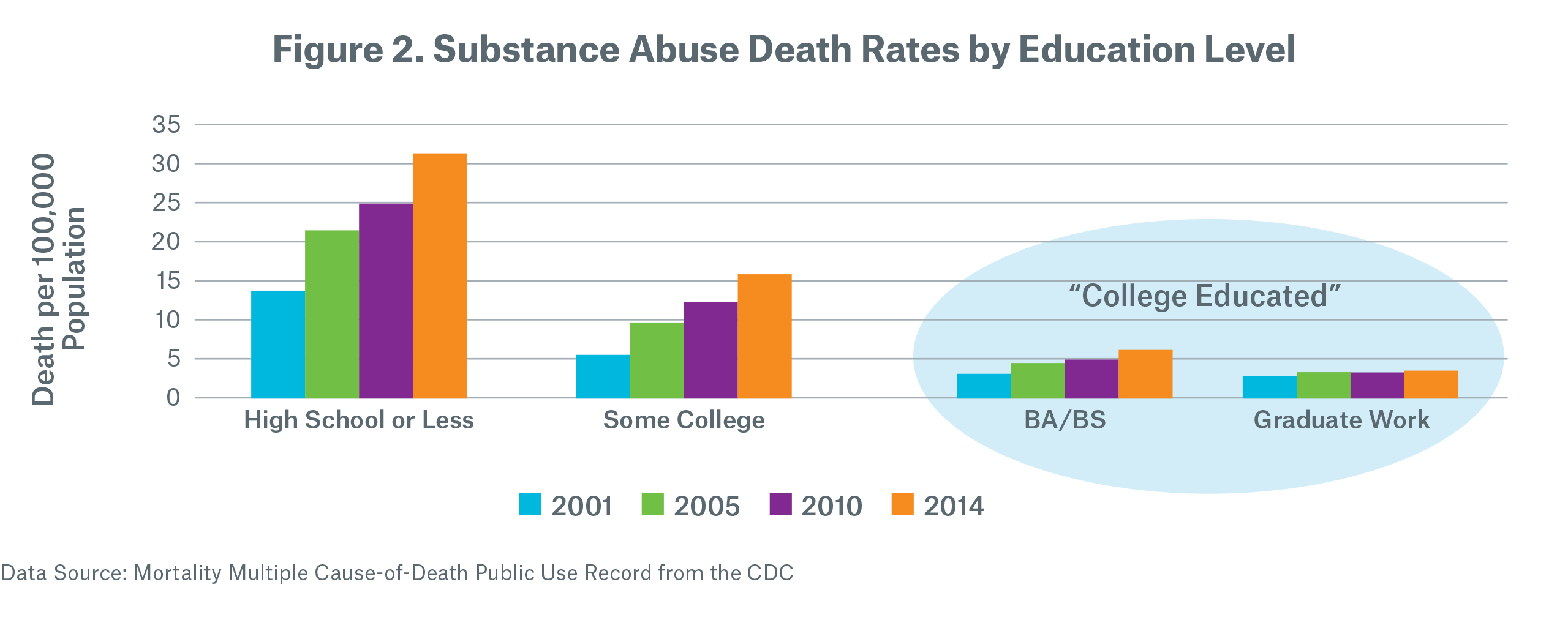

We began our investigation by splitting the population experience to test the hypothesis that socio-economic class was a key differentiator in mortality rates. Since the CDC data did not include any measure of income or wealth, we used the highest educational level attained as a proxy. In Figure 2, we split the mortality rate per 100,000 into four main categories of educational attainment (high school or less, some college, BA/BS degree, graduate work). First, we saw that the mortality rate due to substance abuse decreased significantly the higher the academic attainment. Second, the subsets of the population with the highest academic attainment had the flattest mortality trend over time.

We have not attempted to explain the correlation between higher education and lower substance abuse-related deaths in this

paper.4 We have, however, hypothesized that the college-educated sub-group5 was a good proxy for the insured population, and proceeded to test that hypothesis.

Testing the hypothesis

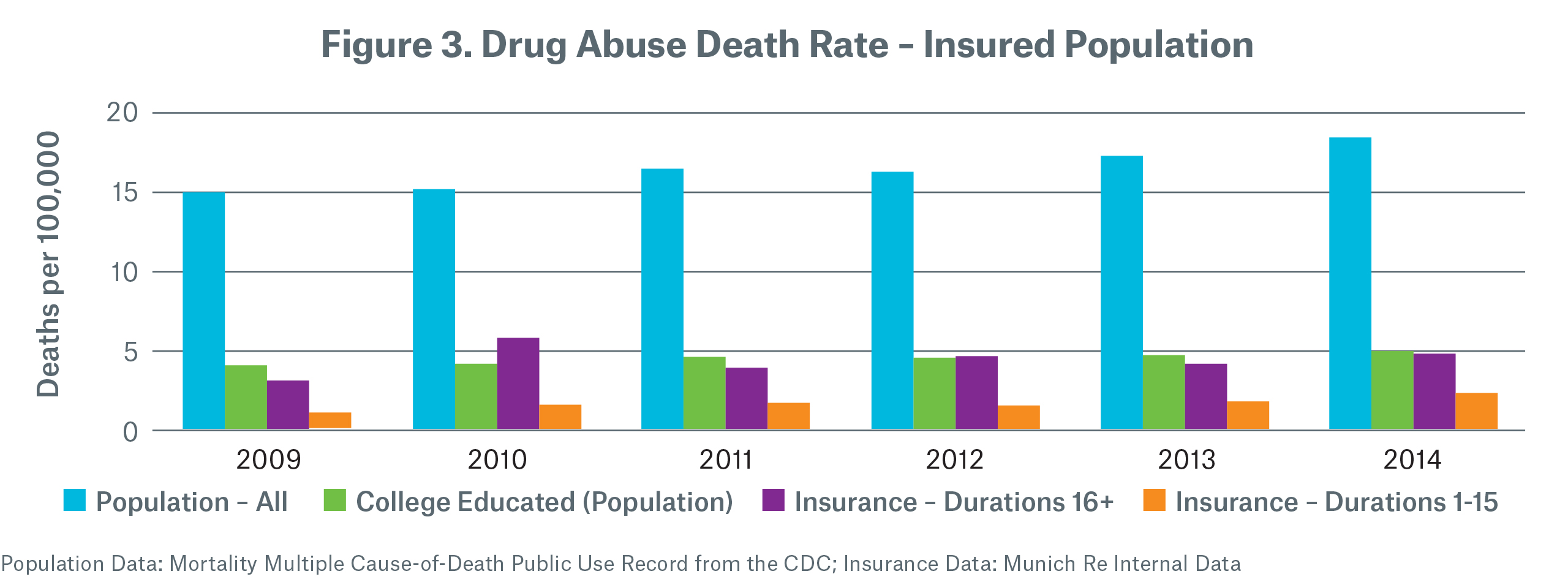

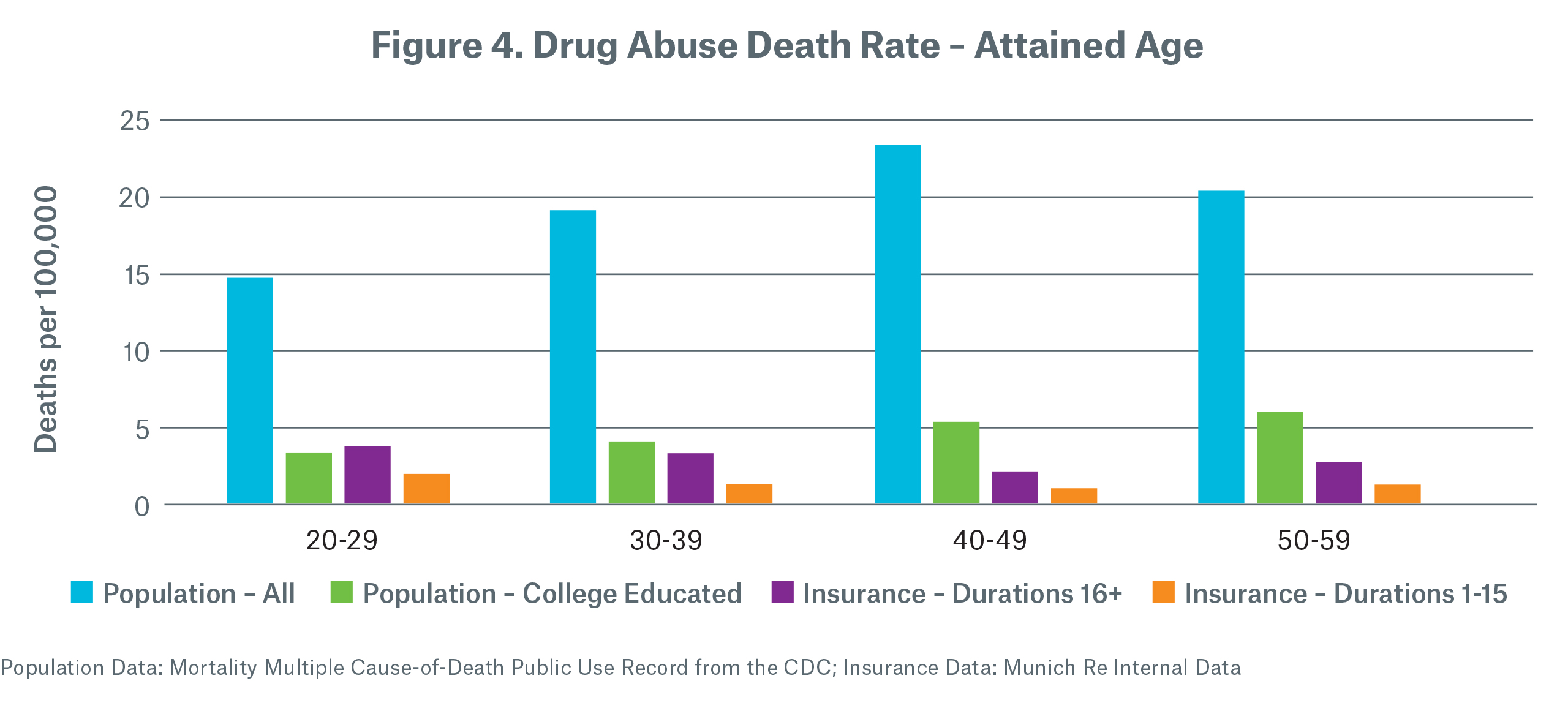

In order to test this hypothesis, we compared the mortality rates for the college educated population with the life insurance claims experience from our own block of reinsurance business split into two segments: first, claims that occurred in policy durations one to 15 (to approximate the select period) and second, claims that occurred in policy durations 16 and later (to approximate an ultimate period). When we looked at the mortality rate by calendar year of death (Figure 3) and then by attained age (Figure 4), we saw that the mortality rate for the college-educated population was a reasonable proxy for the insured mortality rate in the ultimate period. We also observed that the select rate was significantly lower than the ultimate rate, implying that good protective value was already being derived from the underwriting process.

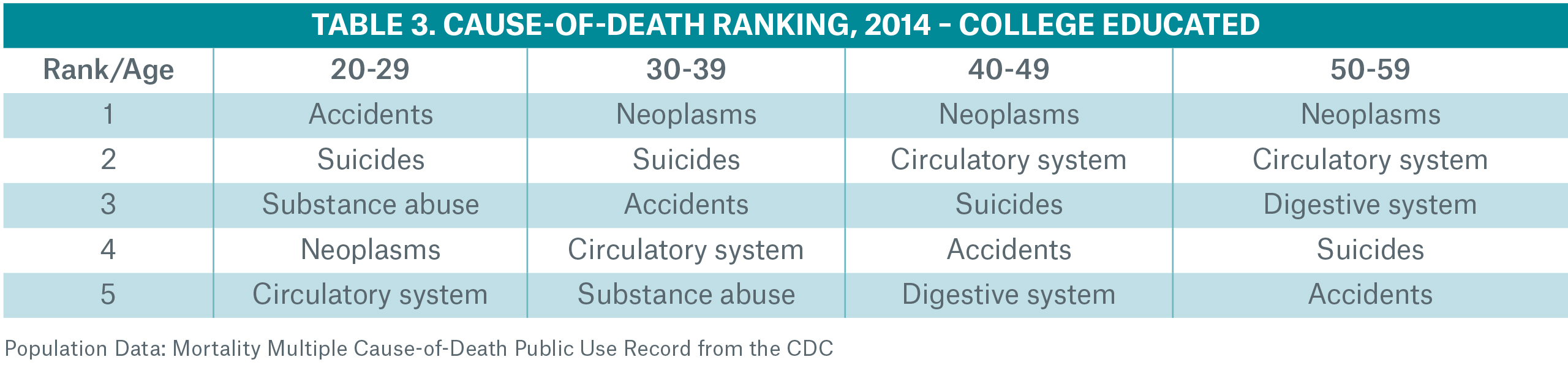

It was also interesting to note the significant change in the cause-of-death rankings between the general population and the college educated population for ages 20-59 (Table 3). Substance abuse moved from first in the general public to fifth in the college educated sub-population for ages 30-39 and was not even in the top five for ages over 40.

Risk selection considerations

This analysis provides evidence that there may be a way to approximate the impact on life insurance mortality using the college educated subset of the population data that is readily available. However, there are some key filters that will be missing in the population databases e.g., smoking class, face amount, issue age and duration. In this section, we will provide some insights into these views using Munich Re’s proprietary cause of death experience study.

Smokers

Typically, the ratio of all-cause mortality of smokers to non-smokers is between 200 percent and 300 percent. When looking at the same ratio for substance abuse only mortality, we see a materially higher differential. By count the ratio for attained ages 30-59 is between 485 percent and 582 percent, and the ratio by amount is between 470 percent and 778 percent. In the Journal of Addictive Disease6, the authors posit that one explanation is that cigarette smoking may be a gateway drug to illegal drug use. Another hypothesis might be that drug users are more likely than not to smoke.

Whatever the reason, this observation might lead underwriters to consider additional drug screening for applicants who test positive for cotinine or lead actuaries to build in some additional conservatism into future mortality improvement for smoker classes.

Duration

We analyzed the substance abuse mortality rate by policy duration to see if the select period showed any evidence of early duration adverse-selection. Adjusting for age, we would expect that the mortality rate would start off lowest in duration one and gradually increase in an exponential curve. The data show this pattern with a noticeable selection effect and no evidence of adverse-selection. We also looked at the percentage of claims that are due to substance abuse, which shows a slightly decreasing trend. This is as expected since as underwriting wears off, medical causes of death such as circulatory system and neoplasm represent a larger percentage of total claims, pushing down the share of substance abuse claims.

Issue Age

We analyzed the mortality rate and the percentage of claims that are due to substance abuse by issue age to see if there were any unexpected spikes in the pattern. For issue ages 10-19 the data show evidence of adverse-selection since there was a jump in both the mortality rate and the ratio of substance abuse deaths to total deaths. Otherwise the pattern is as expected.

Face Amount

The pattern of drug-related mortality rates by face amount shows a declining trend as face amount increases. This aligns with the premise that the higher one’s socio-economic status, the smaller the impact of the substance abuse epidemic. The percentage of claims that are due to substance abuse was relatively constant by face amount.

Moving into the middle market

As companies aim to grow their distribution in the middle market, they need to keep in mind that this segment of the population may not behave as the current insured population. We may find that a different subset of the population data serves as a better proxy for middle market mortality experience and the hypotheses above may not hold for this group. Additionally, as the industry continues toward automated underwriting programs and away from fluid testing, we may be more vulnerable to adverse selection in all areas, including substance abuse risks.

Conclusion

Because of the national level of concern about the substance abuse epidemic there is a wealth of information and data to sift through. At the same time, new screening tools have been developed and it becomes the responsibility of underwriting departments to determine if and when to use such tools. To properly assess changes to the underwriting manual, decision-makers need access to reliable information that can assist in a cost-benefit analysis. Without insured mortality experience that is credible at the substance abuse only level, companies are left to seek information from the general population.

This analysis shows:

- Substance abuse mortality in the general population is significantly higher than insured experience.

- Substance abuse mortality in the college educated subset of the population is a reasonable proxy for insured mortality in the ultimate period.

- Areas of concern are smokers, juveniles and changing distribution methods and target demographic (non-fluid underwriting and middle market sales).

/Tim%20Morant.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/original./Tim%20Morant.jpg)

References:

- Gina Guzman, MD, DBIM, FLMI, FALU. Opioid Epidemic – How did we get here? Munich Re White Paper, 2017. https://www.munichre.com/site/marclife-mobile/get/documents_E-1016841552/marclife/assset.marclife/Documents/Publications/Opioid_Epidemic_Origins.pdf

- CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain — United States, 2016. March 15, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/rr/rr6501e1.htm

- Presidential Executive Order Establishing the President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis. March 29, 2017. https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/03/30/presidential-executive-order-establishing-presidents-commission

- Although it was clear from these data that there was a correlation between education attainment and the impact of the substance abuse epidemic, we could not be sure whether or not there was a cause and effect relationship. It could be that the decrease in drug-related mortality is the effect of the higher socio-economic lifestyles of those who obtain higher education or it could be that these drug addictions start early in life and derail people from plans to pursue higher education. It could also be the case that there is a third factor (or group of factors) that we are not measuring which is an underlying cause. education. It could also be the case that there is a third factor (or group of factors) that we are not measuring which is an underlying cause.

- The union of the BA/BA and graduate work groups.

- Lai, Lai, Page and McCoy. The association between cigarette smoking and drug abuse in the United States. Journal of Addictive Disease,

2000; 19(4): 11-24.